Los Altos Community Center Murals: Concept and Designs

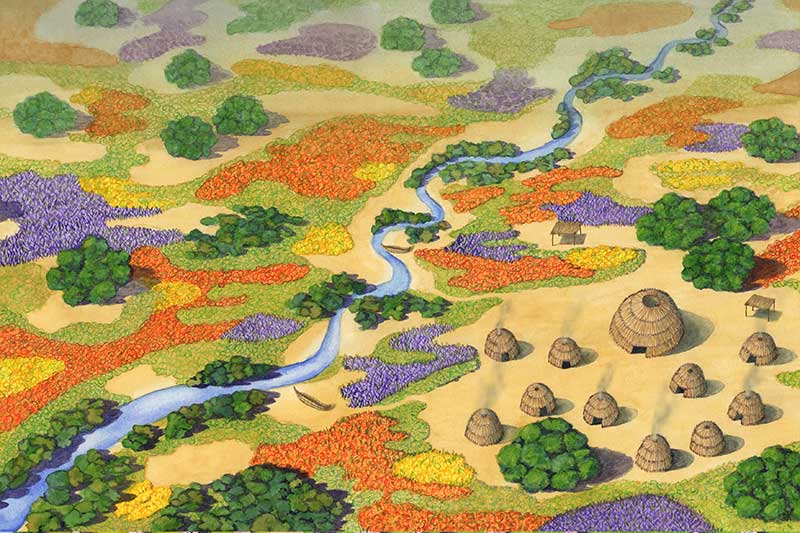

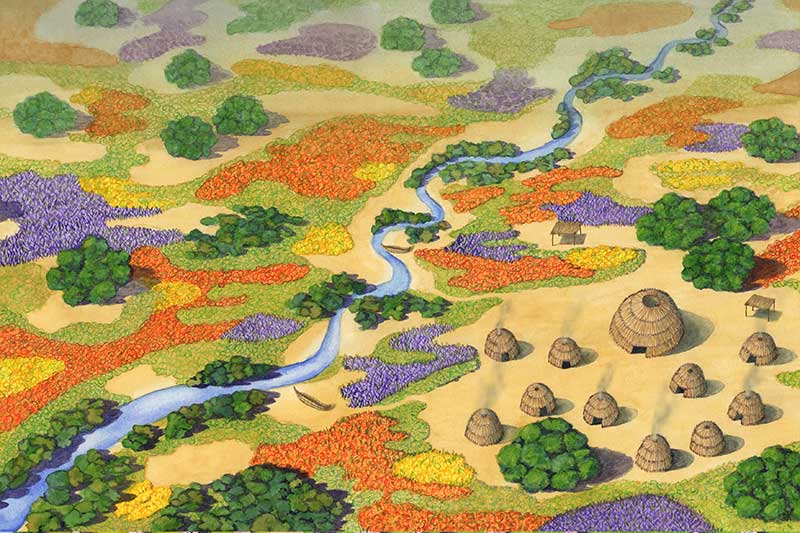

The Los Altos Public Art Commission selected mural artist Morgan Bricca and me to create two murals for the new Los Altos Community Center based on the watersheds of Los Altos; I created the concept and designs, and Morgan painted the murals. The designs reflect the values of the community and integrate with the site. Both murals portray Permanente Creek during different historical time periods: the indigenous landscape and the orchard era. The concept includes the theme of indigenous land recognition. I did extensive research for the designs and consulted with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribal Council to inform the indigenous landscape design and provide an indigenous place name for the creek (used in the mural titles). What differences do you observe between the two landscapes?

* Yákmuy Širkeewiš ’Ooyá Rúmmey (pronounced yahk-moi shee-r-kay-weesh ooi-yah roo-may) is an indigenous name for the creek we now call Permanente and means "East Black Mountain Creek" in Chochenyo/Thámien, the native languages of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco. Bay Area, the descendants of the aboriginal Thámien Ohlone-speaking people who were relatives of the Puichon Ohlone Tribe who lived in the area we now call the City of Los Altos.

The new Los Altos Community Center has been a multi-year and community-engaged process. Noll & Tam Architects created a sustainable welcoming design using natural materials (wood and stone). The colors in my designs were chosen to harmonize with the specified paint colors, carpet tiles and wood finishes.

The nature-based watershed theme in the mural designs relate to the architects' design concept of a "building within a park" and the dry creek bed in the landscape design that meanders from the rear doors of the lobby through the courtyard to the redwood trees to the south.

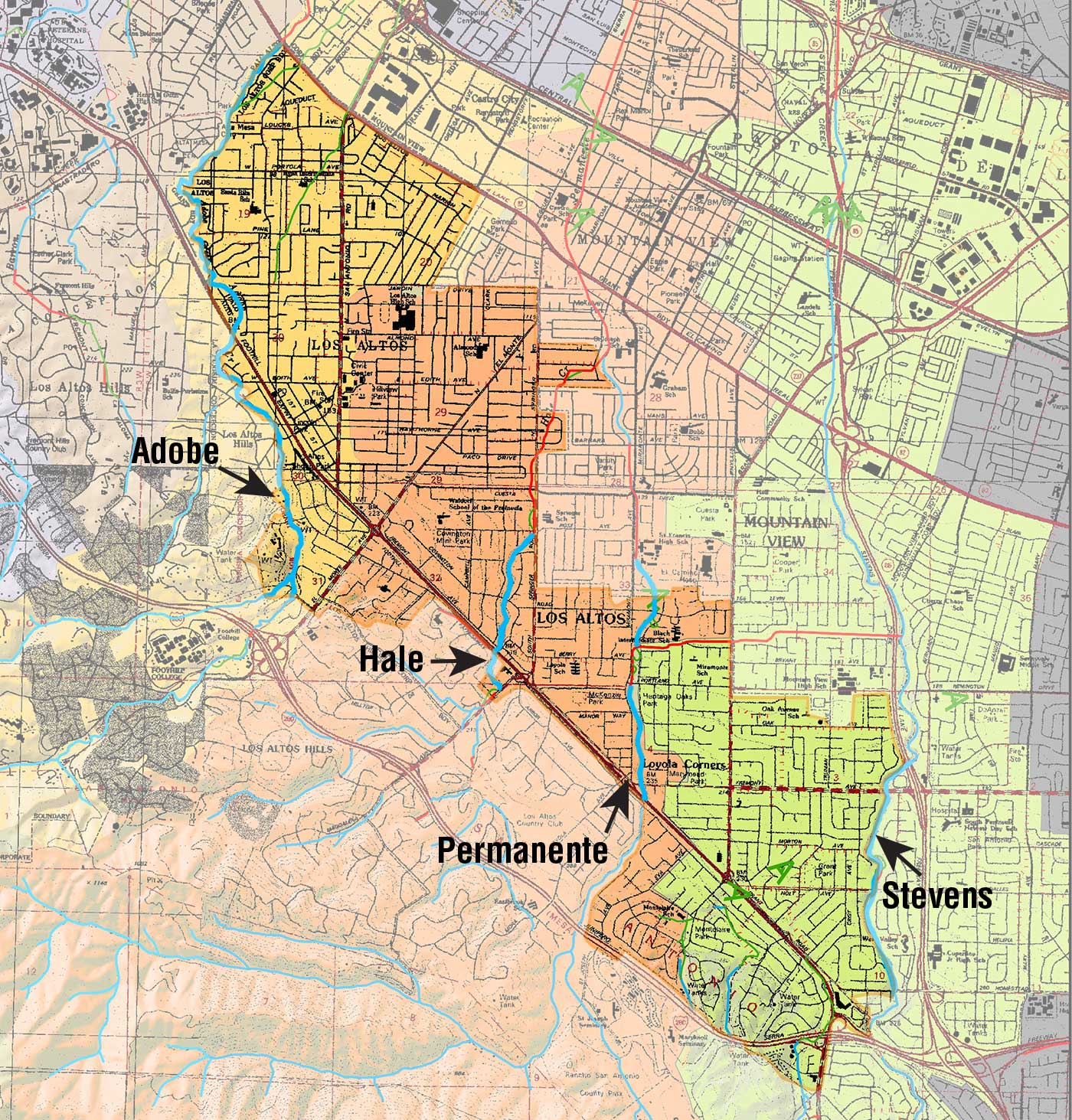

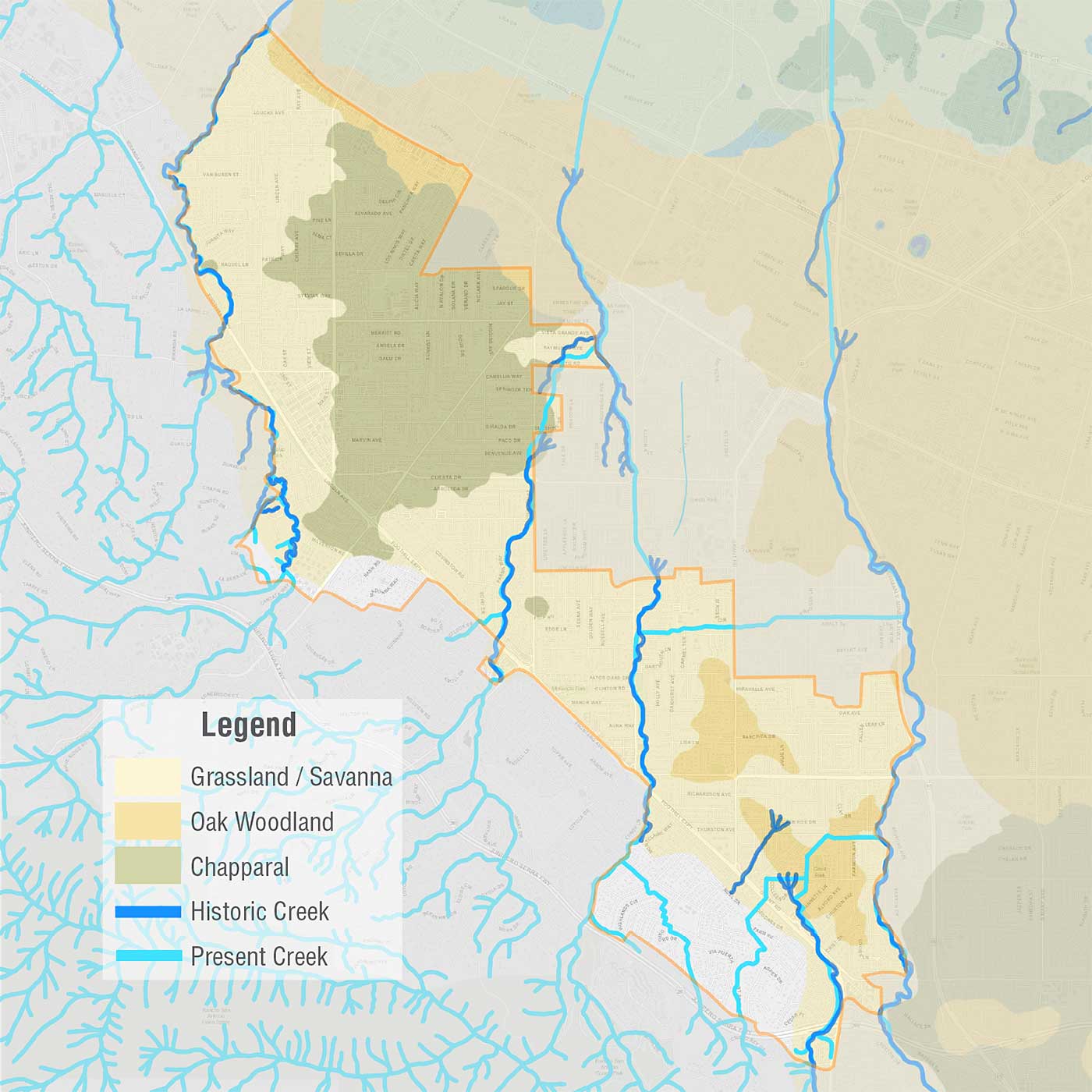

This map shows the creeks and watersheds of Los Altos. Four creeks run through Los Altos; from north to south they are Adobe, Hale, Permanente and Stevens creeks. The boundaries of the city of Los Altos are shown by the lighter shaded area.

Watershed map courtesy of Janet M. Sowers and The Oakland Museum of California

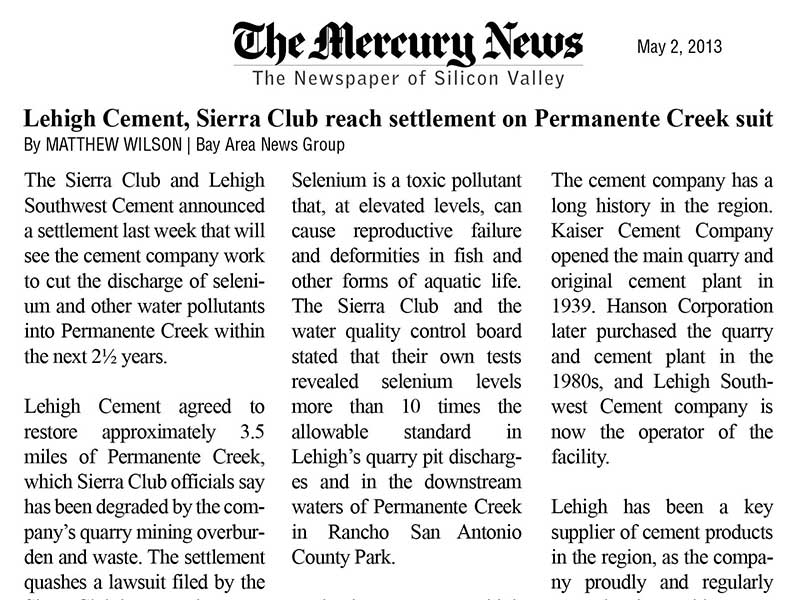

After researching the four creeks, I chose to focus on Permanente Creek for the following reasons: it’s located entirely within Los Altos (Adobe and Stevens form the boundaries with other cities), it’s easily accessible to the public at Heritage Oaks Park, it has been modified over time for irrigation of orchards and flood control and it was the subject of an environmental lawsuit against the Lehigh Cement Company for pollution discharges into the creek.

My research process also led me to choosing two distinct time periods in the history of changes to the landscape: the indigenous and orchard eras. The indigenous landscape was stewarded for thousands of years by the first people to live here, the Puichon. The settler/colonialists brought major changes to the landscape although the changes during the mission and rancho periods were somewhat isolated. Major changes occurred during the orchard era when nearly every acre was planted with fruit trees and the courses of the creeks were straightened and re-routed. This map shows the areas of grassland, oak woodlands and chapparal and the path of the original creeks in the indigenous landscape layered on top of the present-day landscape of roads, highways, and creeks. Notice how the creeks were straightened and re-routed in the last 150 years. Also notice how the indigenous creeks did not flow all the way to the bay; they would fan out into the gravel soils and disappear into the groundwater or spread into wet meadows and marshes before reaching the bay. Only during heavy rains, would the creeks create new channels through the gravel and marshes and flow all the way to the bay.

Source maps courtesy of EcoAtlas, San Francisco Estuary Instititute

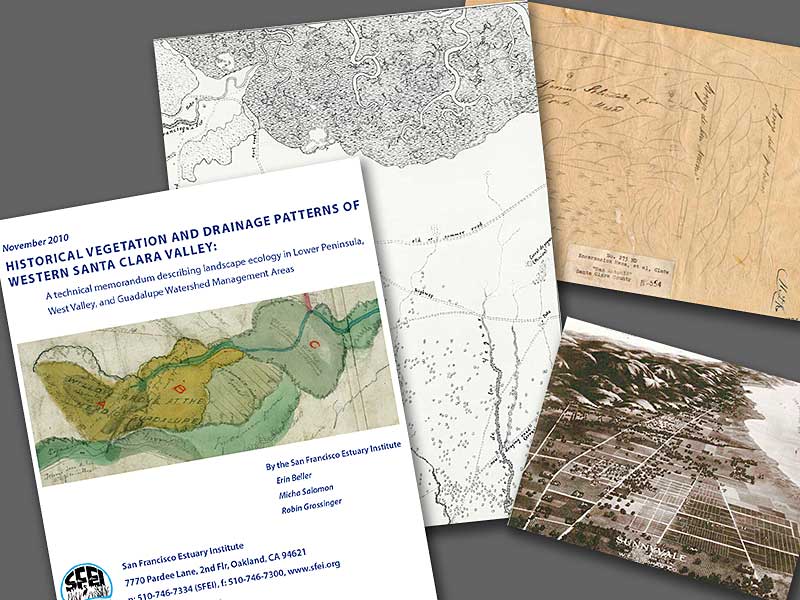

To get a sense of what the indigenous landscape may have looked like, I used historical maps, diseños (primitive Rancho maps) and the “Historical Vegetation and Drainage Patterns of Western Santa Clara Valley” report by the San Francisco Estuary. I recognized that these are settler/colonial resources, so I sought input from the Muwekma Ohlone Tribal Council, descendants of the Tamien who were relatives of the Puichon, to inform my design. The Tribal Council confirmed that the resources I was using were the only known records about the land and provided guidance on the anthropological features in the design. They also provided an indigenous place name for Permanente Creek which was used in the title of the murals.

I read many historical texts to understand the changes to the landscape during the mission, rancho, orchard, post-World-War-II, and Silicon Valley eras. The orchard era is remembered fondly when the Santa Clara Valley was known as “the Valley of Hearts Delight.” The earliest complete aerial photography of Los Altos is from 1948, before Los Altos officially became a city and the land around Permanente Creek was still planted with orchards. I used this imagery to inform the orchard era mural design.

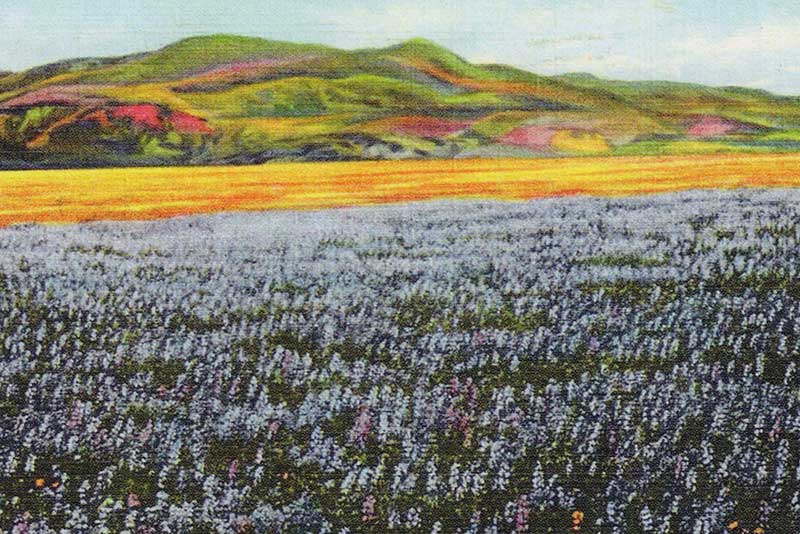

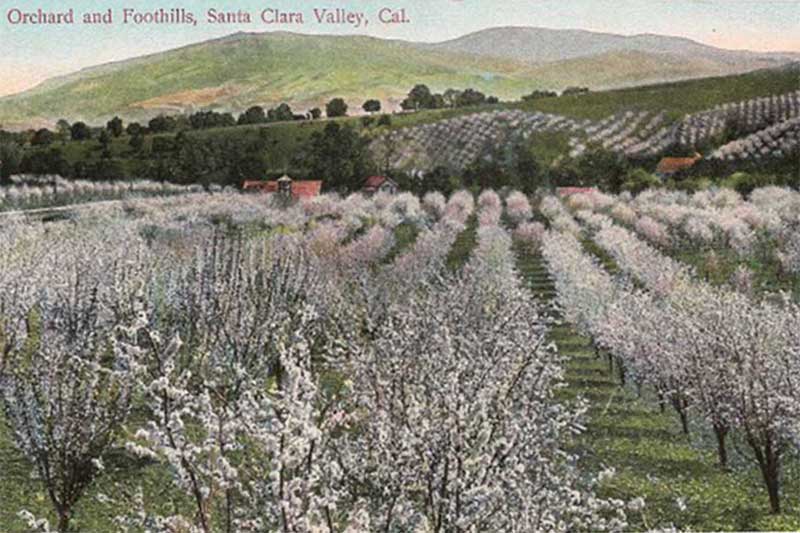

I chose the season of spring for both murals. Several nineteenth century travelogue accounts describe the spring historic landscape as carpeted with wildflowers. The spring orchard landscape was filled with fruit trees blooming in pink and white blossoms. You can get a sense of the beauty in these vintage postcards of the Santa Clara Valley.

The landscapes of these different time periods contain both beauty and complicated histories. Many people reflect fondly on the Valley of Hearts Delight yet, all that remains of the indigenous landscape are a few oak trees; they persist, strong and proud, like the survivors of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe today. Most indigenous grasses, plants, animals and fish are gone and the creek has been straightened and channelized. In the words of ethnic studies professor Dr. Charles Sepulveda (Tongva and Acjachemen): “Both the native people and the creeks were seen as wild, uncivilized, non-human and ready for domestication: to be bent to the will of white supremacy in order to benefit ‘white life.’

* Yákmuy Širkeewiš ’Ooyá Rúmmey (pronounced yahk-moi shee-r-kay-weesh ooi-yah roo-may) is an indigenous name for the creek we now call Permanente and means "East Black Mountain Creek" in Chochenyo/Thámien, the native languages of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco. Bay Area, the descendants of the aboriginal Thámien Ohlone-speaking people who were relatives of the Puichon Ohlone Tribe who lived in the area we now call the City of Los Altos.

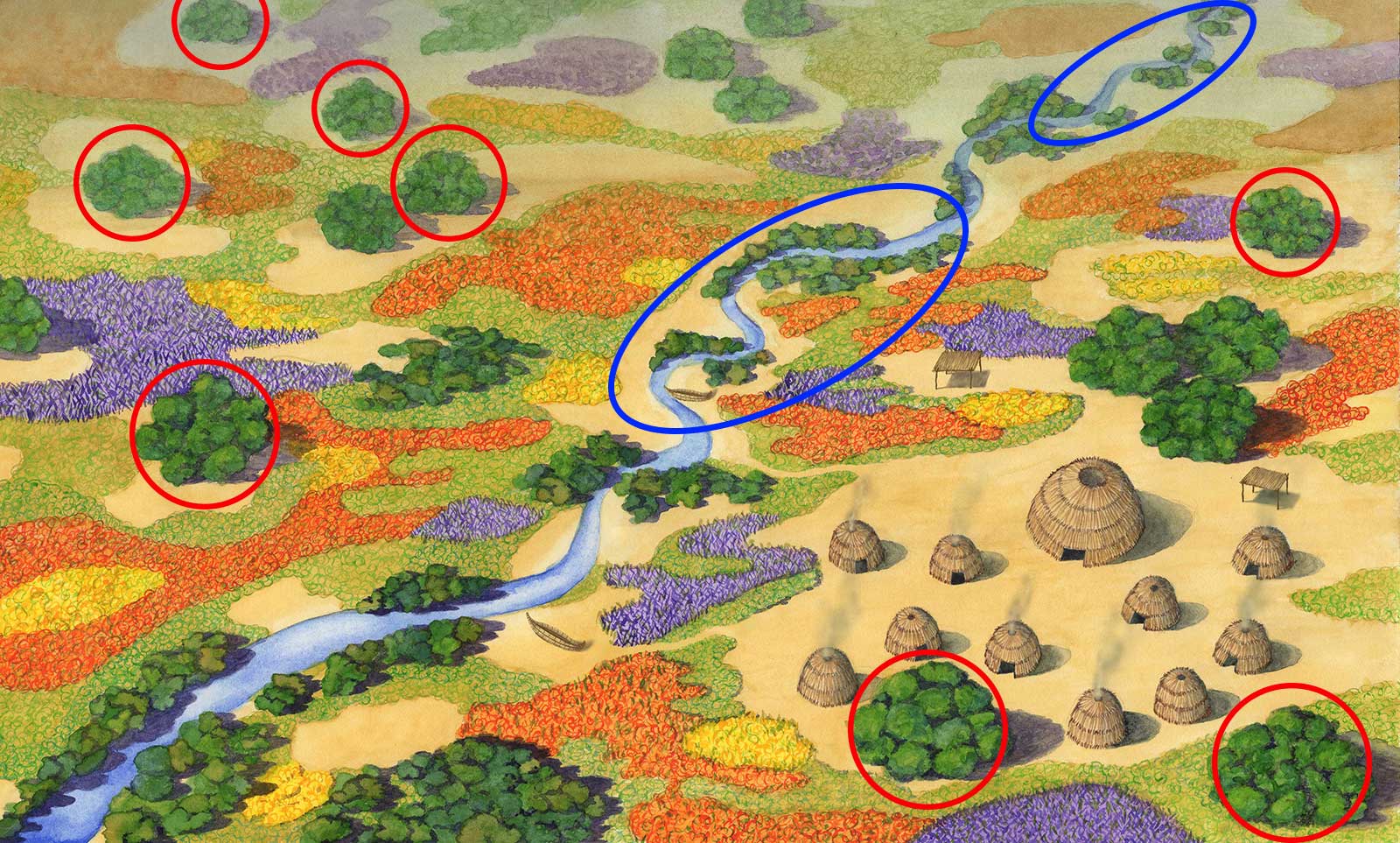

Move the blue dot above from left to right to observe the changes between the indigenous and orchard era landscapes. The indigenous landscape is grassland and oak savannah with large oak trees dotting the landscape. There are some willows near the creek and carpets of poppies, lupines, and goldfields. This was a fire managed landscape so there are few areas of dense brush. There is a Puichon Ohlone village in the lower right foreground, near, but not next to the creek because of flooding. The red circles mark where large oaks were in the indigenous landscape. Observe how many of the large oaks are gone in the orchard landscape, having been logged for firewood and construction. The blue circles highlight changes to the creek. In the orchard era landscape, observe how the creek is straighter. Other changes include dense overgrowth of creek vegetation because cultural fire management practices were outlawed more than 100 years before; gaps in the orchards where large oaks once stood because fruit trees cannot grow in oak root fungus; areas of bright yellow non-native mustard flowers blooming in the fields along with a few remaining fields of poppies

Timelapse video of painting the watercolor design for the indigenous mural.

These are mockups of the mural designs in the architects’ renderings of the interior of the community center. We placed the indigenous mural in the north lobby because the openess of the landscape matches the large open feeling of the lobby. We placed the orchard mural in the intimate seating area in the south lobby.

These are the final murals as painted by Morgan Bricca. The community center opened its doors to the public on October 2, 2021 and it's exciting to have this artwork as an integral part in this special new gathering place for the community. The 24,500 square building includes dedicated space for senior, teen, and kindergarten preparation programs, as well as flexible indoor and outdoor community gathering spaces.